In my first article in the blog from PERSEO project, I have introduced my project distinguishing personalization from customization. As a reminder, personalization is a system-driven sort of adaptation where the robot autonomously adapts to its user. Customization is a user-driven adaptation process where the user adapts the robot to their own preferences and needs. In my theoretical model, I hypothesized that personalization increases trust towards an adapted robot because of anthropomorphization – the ascription of human characteristics to the robot – and customization does so because of psychological ownership – the subjective feeling of owning the robot. This model made sense from the theoretical point of view, and the first experiment I performed during my Ph.D. provided support for my predictions regarding customization increases psychological ownership of the robot, which in turn increases trust toward it [1].

However, something appeared wrong with that model. There are multiple cases of robots whose adaptation to their users rely on both its programmed autonomy and the involvement of the user. For instance, Learning from Demonstration is a technique whereby a robot learns how to perform a task after being shown by a human how to achieve it, implying that the robot adapts to how its user teach it the task. In human-robot interactions (HRI), the personalization vs. customization dichotomy seems insufficient to describe how adaptation can influence how we perceive and interact with robots.

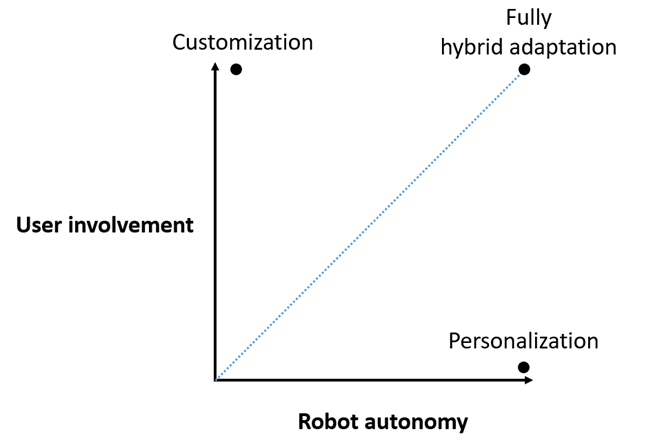

So what? Should we throw this inconvenient dichotomy away? My answer is not exactly. Although it is true that personalization and customization as categories do not embrace the complexity of robot adaptation to their users, they allow to isolate two important factors that we can find in every sort of adaptation to various extents: user involvement, and robot autonomy.

Robot autonomy can be defined as “the extent to which a robot can sense the environment, plan based on that environment, and act upon that environment, with the intent of reaching some goal (either given to or created by the robot) without external control” [2]. Robot autonomy is prone to elicit anthropomorphization of the robot. From this follows that any adaptation process based on robot autonomy should elicit ascription of human characteristics to the robot.

I address user involvement as twofold: First the extent to which people invest themselves in a product or system in order to influence its characteristics, which can be referred to as objective user involvement. This objective involvement can result in the perception of being involved, which can be referred to as subjective user involvement. Involving individuals into an object or a project leads to increase their self-investment into it, as well as their perceived knowledge about and control over it. These effects of user involvement are known to be determinants of psychological ownership.

Distinguishing user involvement and robot autonomy in adaptation of robots to their user was motivated by the need to find a proper taxonomy that would encompass adaptation processes that cannot be labelled customization or personalization because they can be deemed both. By considering robot adaptation as being in a bi-dimensional continuum of robot autonomy and user involvement, it becomes possible to sort adaptation processes based on how autonomous the robot is in the adaptation process and how involved the user is. This approach would also grant the possibility to identify which factor between robot autonomy and user involvement in adaptation is preferable depending on the kind of user the robot has to be adapted to. For instance, people with higher affinity for technology and concern for privacy – also known as power users – are more likely to prefer customization over personalization, hence suggesting that user involvement should be preferred when targeting power users.

Fig. 1. The robot autonomy – user involvement continuum. With such a visualization, it becomes possible to sort different adaptation processes, under the condition of testing the extent of to which a given adaptation process implies user involvement and robot autonomy.

The curious reader can find the early bases of this proposed approach of robot adaptation in a late-breaking report we have written [3]. The take-away message here is that adaptation can have multiple shapes, but each of them imply some extent of robot autonomy and user involvement, which, in turn influence how people perceive and react to an adapted robot. And whereas several works address the positive influence of robot autonomy on human-robot interaction when adapting themselves to users, not so much is done to understand how involving the user in robots’ adaptation processes can contribute to elicit more positive perception of robots and help to have them accepted, trusted, and used. I therefore advocate for a better account of user involvement in future research.

References:

[1] D. Lacroix, R. Wullenkord, and F. Eyssel, ‘I Designed It, So I Trust It: The Influence of Customization on Psychological Ownership and Trust Toward Robots’, in Social Robotics, F. Cavallo, J.-J. Cabibihan, L. Fiorini, A. Sorrentino, H. He, X. Liu, Y. Matsumoto, and S. S. Ge, Eds., in Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022, pp. 601–614. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-24670-8_53.

[2] J. M. Beer, A. D. Fisk, and W. A. Rogers, ‘Toward a framework for levels of robot autonomy in human-robot interaction’, J Hum Robot Interact, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 74–99, Jul. 2014, doi: 10.5898/JHRI.3.2.Beer.

[3] D. Lacroix, R. Wullenkord, and F. Eyssel, ‘Who’s in Charge? Using Personalization vs. Customization Distinction to Inform HRI Research on Adaptation to Users’, in Companion of the 2023 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, in HRI ’23. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Mar. 2023, pp. 580–586. doi: 10.1145/3568294.3580152.